How Two Become One: A Qualitative Review of the Use and Perceptions of Weight Bearing/Giving, Touch, and Visual Contact in Dance Partnering

By David Outevski

An extract from MSc thesis

Glossary

Touch Physical contact that does not involve full weight bearing or giving, e.g. holding hands.

Weight bearing Physical contact that involves taking some amount or the whole & giving weight of the partner, e.g. a lift.

Visual contact No physical contact, use of visual sense to relate to the partner, e.g. mirroring (copying the partner’s movement without touching).

Dance partnership Two interactively moving bodies in dance practice

Biomechanics The science concerned with the internal and external forces acting on the human body and the effects produced by these forces. (Brianmac, 2011)

Abbreviations

Terms

TWV – Touch, weight bearing and giving, and visual contact

Interview Participants

CI1 First contact improvisation professional

CI2 Second contact improvisation professional

CI3 Third contact improvisation professional

T Tango professional

B Ballet professional

B1 Second ballet professional

BL Ballroom professional

Introduction

The aim of this study was to analyze the role and importance of touch, visual contact, and weight bearing/giving (TWV), within dance partnerships. The dance styles observed consisted of ballet, ballroom, Argentine Tango, contemporary and contact improvisation.

The data collection was conducted by means of an extensive literature review, class/rehearsal observation and video recording, as well as through an online questionnaire and qualitative interviews with dancers and teachers. The first goal of the study was to establish a context for the research whereby the current state of knowledge on the subject of partnering could be examined by analysing and synthesizing the materials gathered during the data collection stage. The second goal of this study was to attempt to propose ideas and actions for the development of the aforementioned elements in dance partnering by drawing on strategies used by the various professionals and the understanding gained from the research and literature review.

Movements and relationships were analysed from a general movement perspective with such actions as: holding, touching, looking, lifting, jumping, and pushing/pulling, considered the basic elements in partner work common between dance styles.

With this research an attempt was made to answer questions such as: how is connection or contact used in different dance styles? Are the same aesthetic and sensory qualities valued between styles? And can the insights from one dance style be useful in another?

Rationale

Partnerwork is an essential part of most dance styles. In several styles it is an addition to the general dance vocabulary while in others it is the main component. While the majority of dancers would probably agree on the general importance and benefits of partnerwork, many have specific opinions on how it could be taught and what is important for the development of a good duet. From a ballroom/Latin background perspective where everything is done with a partner it seems only logical that a better understanding and use of the biomechanics and sensory perceptions involved in partnering would greatly improve the quality of movement for the dancers when they dance with another body as well as increasing the artistic and technical output given by such performances. Despite the fact that most dancers are likely to be in accord with the above statement, the dance population generally seems to dismiss this topic as a given and common knowledge while still often failing to interpret, explain or at times even execute it correctly within the realms of their respective experience. Everyone knows that one must ‘feel’ their partner in order to create good partnering but what exactly is that ‘feeling’ and how can we consistently and systematically produce it?

The literature review indicates that there seems to be a lack of specific research in this area. While there are many technical articles on the ballet duets, journal writing on contact improvisation, and Latin and ballroom technique books that all provide certain information about the topic, not many address it without genre specific technical reference or as a movement analysis involving all the elements examined in this study. Separately these works serve their purposes in their disciplines however if this information could be gathered, linked, and shared, the benefits might be great to partner work in all styles. Better understanding of overall partnering skills would bring more security on stage, more feeling of comfort between partners and more mental space for the performance itself rather than concerns about the technical aspects of lifts, holds, and other partnering skills.

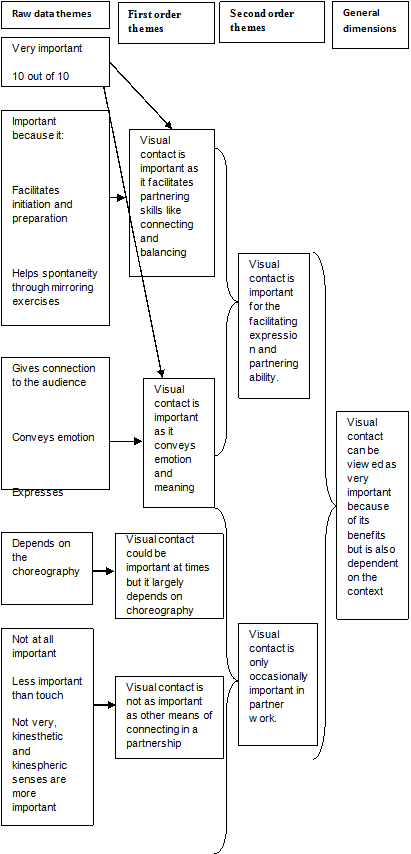

Following is a thematic diagram from the questionnaire responses on visual contact followed by the interview answers on the same topic. A discussion of these results in relation to available literature is then presented.

Question 8: How important do you think visual contact is for partnering in dance?

Visual contact – interviews

CI1 – Training with eyes closed at first might reduce anxiety related to touch and bring more sensitivity in contact improvisation practice, yet when a practitioner is sufficiently experienced, eye contact can be brought in to increase the use of surrounding space, safety, and add another method of communication to the dance.

T – Eye contact is more about meaning. It brings me to another element that is spiritual, I can’t just dance with everyone, there has to be a deeper connection and understanding.

BL – Visual contact helps leading and following and allows the principles of ‘cue and resistance’ to be transmitted visually as if your partner was touching you visually.

B – The visual as well as physical connection can change with the role played in the choreography. In a romantic story such as Romeo and Juliet for example both partners act and look at each other as if they are in love while in a different story such as Spartacus or The Hunchback of Notre Dame the male partner might act proud or pitiful accordingly and the female partner can look at him with desire or kindness. Another element can be the personality of the dancers. If the male partner has a narcissistic attitude for instance, even good technique will not hide his lack of care toward his partner both in visual and physical expression.

Discussion

Visual Contact in partnering

Vermey argues that bodily communication and expression are fundamental in partner dancing and uses Michael Argyle’s (1975) bodily communication categories of: facial expression, gaze, gestures and other bodily movement, posture, bodily contact, special behaviour, and appearance as the fundamentals of this communication (Vermey, 1994, p.91). He describes how the type of gestures like direct or non direct gaze, asymmetrical touching, and special positions are the products of this bodily communication (Vermey, 1994, p.93). Gaze and facial expressions seem to play a large part in this analysis, yet visual contact was the most disputed of the three elements discussed in this research. 54.54% of the dancers considered it important for partnering while 45.46% either did not think it was important or said that it was only important occasionally. The meanings and purposes of it were also varied with physical partnering skills like connecting or balancing being the result of visual contact at 36.36%, and the conveyance of emotion and meaning at 18.18%.

Further, 23.37% stated that the purpose of the visual contact depended on choreography and 23.37% did not consider it as important as other means of partnering. T echoes the views of those who emphasize emotion and meaning when she states that visual contact “brings me to another element that is spiritual, I can’t just dance with everyone, there has to be a deeper connection and understanding.” While the BL states that it can develop spontaneity and be like the ‘visual touch’ in partnering, expressing the second view where visual contact is used for enhancing the physical connection to your partner. CI1 states that visual contact is important more in the advanced levels of contact improvisation than at the beginning as it can distract beginners from using their other senses.

Similarly, in the ballet class observation, visual contact was addressed only once the choreography was well rehearsed. In this case though, visual contact was used mainly for dramatic expression. This ‘role playing’ within partnering is characteristic of stage duets in classical ballet in particular, it emphasizes the expression of the relationship required by the role played rather than actual relationship between partners within the dance as can be seen in Argentine Tango for instance. Nevertheless, since dramatic expression can affect movement, partnering can also be enhanced by such expression.

Stylistic differences seem to emerge here, visual contact overall seems to be more important to ballroom dancers as 83.33% of them stated it being important either for emotion and meaning or for physical and technical aspects of a partnership, and none considered it unimportant. Of the contemporary and ballet dancers on the other hand only 37.5% considered it consistently important while another 37.5% thought it was not very important in partnering. This can possibly be explained by the fact that in ballroom and Argentine Tango dancers often dance with the same partner for long periods of time and mostly in some kind of a hold, while in ballet and contemporary partners often change (Lewis, 2008, p.72) and duets can often involve work apart where dancers do not physically touch but still move in relation to each other.

Further, sometimes there can be an intentional lack of visual contact in order to emphasise a choreographic demand such as when dancers need to express indifference to each other. These differences influence how visual contact is perceived and justify the divergences of opinions in the responses to this question. When visual contact was considered necessary several strategies were proposed for its use and improvement.

From the answers to the questionnaire, mirroring each other’s movements and improvising without touching seem to be the most used exercises for the improvement of visual contact in a partnership in all styles. Conscious awareness and practice of emotional expression and communication through eye contact and facial expression were also mentioned as training strategies. This is reflected in the B’s interview where he points to the fact that eye contact in ballet changes according to the role played whether it is romantic, pitiful, or angry and the expression of these states can be trained as it is done by actors in order to improve visual contact and presentation.

Outlining these strategies is important because even in styles where eye contact plays a major role, like ballroom, the specific training of it is often neglected. As Vermey (1994, 1994, p.89-90) explains, a preoccupation with technique has distinguished competitive ballroom dancing from its social roots. This separation caused the dancers to ignore the bodily communication inherent in its vocabulary that includes gaze, focus, and posture as some of its main components. Even in cases where eye contact is the not a prioritized form of connecting in a certain style or specific choreography, it is impossible to ignore its expression.

Indirect gaze or even deliberate non-gaze are expressive of something and cannot be said to not play any part in a dance partnership, they must be considered gestures just like physical movements. As Humphrey (1987, p.110-112) asserts, visual communication happens through the inherent motivation behind the use of the visual sense and therefore necessarily has meaning behind it even it is to express the absence of it. Visual contact is also particular because in contrast to touch and weight sharing in partnering, it does not require physical contact to be expressed or understood, therefore requiring subtle attention to its use that is too often neglected by dancers.

An awareness of these aspects of visual contact suggests the importance of this often ignored element in partnering. For example, if the choreography requires the dancers to ‘see each other’ just looking in the direction of the other’s eyes or body will not do, one must be aware of the partner and his or her response to the gaze in the same way the partner in question must be aware of being watched and respond accordingly in whatever way the choreography demands. (Winkelhuis, 2001, p.45-46) Conversely, in a case where visual contact is not emphasized or deliberately not used both dancers need to be aware of the meaning behind this ‘non-looking’ and understand the visual, emotional, and physical impacts that such presentation will produce in themselves and the outside observer in order to make it effective.

David Outevsky