By Ilya Vidrin, PhD

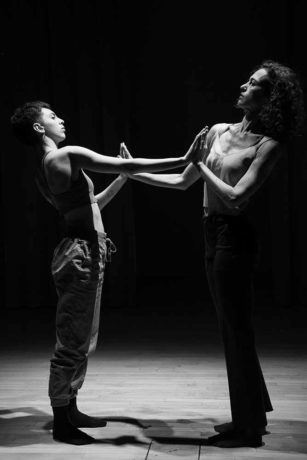

Trust and care are two concepts that frequently come up in conversations about partnering. Yet, when asked to articulate the difference, language often falls short. On the surface, there is a tendency to believe that what we say shouldn’t matter as much as how we express care and trust through action. But time and again, I have seen that how we conceive of these two concepts is incredibly significant to what actually plays out in practice.

From minor bickering and missteps, to major conflicts and even injuries, labeling trust and care as merely abstract principles can have harmful consequences. After extensive research in cognitive neuroscience, social psychology, and philosophy of interaction, I discovered a few key points that help distinguish trust and care in order to support a more effective and ethical partnering practice.

“Trust is not always a good thing”

I’ll be the first to admit that this statement took me a bit by surprise. But when I think critically about partnerships, I recognize that trust can be blind. The results of blind trust can be incredibly beautiful when successful—like in trust falls, we experience the rush of not knowing and the relief in being caught. But the parameters are something everyone must agree to in advance, specifically because the one blindly trusting is taking on a more passive role than the ones catching. Others have to be more alert in order for this passivity to be possible.

For choreography that relies on active participation from all dancers involved, blind trust is a major obstacle because we miss out on paying attention to key factors like timing, musicality, and even accidental missteps. When one partner blindly trusts that the other will be on beat, they often stop tracking movement. This interferes with synchronization and coordination. If a dancer blindly trusts that the orchestra will play live like they do on the recording, the dancer will stop listening to the music. If partners blindly trust each other that everything will go well, then minor missteps can lead to major injuries.

While trust is certainly a key component of partnering, it is important to identify when it is blind. One way to do so is to begin rehearsal with basic weight-shifting and weight-sharing exercises, which can help partners calibrate to each other even if they have danced together many times before.

“Everything you do matters, no matter what you do”

When teaching or coaching, I use this statement to introduce the concept of care. As dancers, we often have to balance care for a number of different things at the same time. Care for our partners, care for the execution of movement, care for musicality and timing, care for our bodies, care for our audience, to name just a few.

Caring for the partnership accounts for more than just caring for one’s partner. If we try to make movement easier for each other, we may end up trying to do things on our own. By holding back or taking on too much, we place ourselves and our partners at risk.

A challenging aspect of care is that it refers to both an attitude and an action. We say things like “I care about you,” but in my experience, finding something meaningful is not enough—we need to practice effective strategies for expressing care through our actions. This is sometimes easier said than done, especially given that we have to rely on others to be willing and open to communicate what is and is not working. The common adage “practice makes perfect” is a bit misleading in partnering because it is not always clear what needs to be honed and refined in complex interpersonal movement.

One of the biggest takeaways I have from my research in cognitive neuroscience is that practice makes permanent. When we let our frustration overtake our care for others and ourselves, or our care for subtle timing, execution or our audience, we are essentially practicing a lack of care. Yet ironically, frustration is also a demonstration of care —if we didn’t care so much, we wouldn’t get so frustrated!

There are many simple ways to practice care to calibrate our attitudes and our behavior. For example, when getting dressed for rehearsal, folding or rolling up clothing is a simple way to practice care. The more we can appreciate small, subtle actions, the more practice we have to make care permanent.

“Be prepared for anything”

On the surface, this statement is also fairly obvious. Yet in my research, I have seen that dancers often prepare for the worst. When we expect bad things to happen, we essentially psych ourselves out. We start to focus on all the errors and mistakes, which can lead to assigning blame to ourselves or others. By preparing for the worst, trust and care both go out the window.

To be prepared for anything means being alert and grounded, adjusting to circumstances fluidly, and setting aside expectations, assumptions and biases. To be prepared for anything is to be in dialogue with ourselves, our partners, and the conditions in which we rehearse and perform.

There are many simple ways to prepare for the unexpected. By practicing the same movement at different speeds, wearing slippery socks, barefoot and in shoes, we can start to get a grasp for the way our bodies react to change. Improvisation is also a great way to practice being prepared for anything, as long as we continue to surprise ourselves, too!

I have personally seen the way in which these three ideas can change not just the quality of movement, but the quality of interaction between partners. Whether dancers are just starting out or are seasoned professionals who have partnered with the same artists for years, the ethics of partnering requires focused attention and vulnerability. Though developing chemistry between partners is still a matter of hot debate, there is plenty that dancers can do to ensure mutual safety, shared understanding, and reciprocal artistry.

About the author

Dr. Ilya Vidrin is a first-generation choreographer, researcher, and educator at the intersection of performing arts, philosophy, and interactive media. Born into a refugee family, Dr. Vidrin’s research and artistic practice interrogates the complex ethics of human interaction, including the embodiment of empathy, cultural competence, and social responsibility. He is an alum of Northeastern University, where he pursued undergraduate studies in Cognitive Psychology and Neuroscience. He completed graduate work in Human Development and Psychology at Harvard University, and a doctorate in Performing Arts at Coventry University in the United Kingdom. He has been artist-in-residence at Jacob’s Pillow, the National Parks Service, AREA Gallery, Harvard ArtLab, MIT Media Lab, The Walnut Hill School, Interlochen Arts Academy, New Museum (NYC), and the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston).