This article first appeared in a series called Perfect 10 in Dance Today (www.dance-today.co.uk)

By Alison Gallagher-Hughes

It’s a dance that has constantly evolved amidst a tussle of tradition, authenticity and innovation. Like most of its Latin brethren, the rumba emanated from Cuban origins, which fused together the African rhythms and Spanish influences of its inhabitants. But France was to play a pivotal role in bringing it to these shores.

At the turn of the 20th century, Paris was the hub of European society. Its rich social tapestry and colonial influences meant that many new dances were generated in the French capital.

He took the essence of the dance and developed it into something that could be adopted by polite society and so was born the square rumba

One such exponent was Pierre Zurcher-Margolle. During the 1920s he attended the clubs and dance halls of Paris that were also frequented by immigrants from Cuba, Brazil, Argentina and Spain. He came to love the unfamiliar rhythms and moves. He took the essence of the dance and developed it into something that could be adopted by polite society and so was born the square rumba, which he introduced to London through teaching and demonstrations.

Monsieur Pierre and his partner, Doris Lavelle, became pioneers of Latin American dancing, developing them around the box step that had emanated from the first “couple dance”, the waltz.

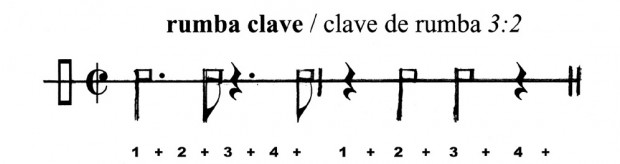

In her book Latin and American Dances, Lavelle recalls how Pierre’s initial teachings needed to be revised when, on a visit to Cuba in 1947, he discovered that the locals “were not happy with the rhythm he was using” and realised that the dance was commenced on the second of its 4/4 beat and not the one!

The popularity of Latin dances was spurred on by political and social change. Philip J S Richardson notes in The Social Dances of the Nineteenth Century that there was a “curious example of cause and effect”. He writes: “It has been said that the existence of Prohibition for many years in the States, by sending thousands of thirsty pleasure-seekers cruising to the West Indies, put New York society in touch with the rhythms of the South, and so expedited the arrival of such dances as the rumba in the ballrooms of the world.”

The emerging prevalence of Latin within the ballroom genre resulted in the formalisation of syllabus and technique. Leading lights such as Pierre, Walter Laird and Dimitri Petrides laid down the foundation on which the form could grow.

In 1960 the first Latin competitions were held, but these early days were not without their problems. The emergence of Pierre and Doris’s Sisterna Cubano in 1948 – with its back and forward breaks – had overtaken the box rumba in the UK, but it was slow to catch on in the rest of Europe.

The “Rumba War”

Brigitt Mayer-Karakis chronicles this in her book Ballroom Icons: “In places like Germany it took much longer to establish and for a time you would see some competitors such as Wolfgang Opitz dancing the rumba box sharing the floor with others such as Axel Germind performing the new style,” she says.

This resulted in the outbreak of a “Rumba War” with some teachers fighting for the new version and others wanting to retain the old. Leading lights such as Nina Hunt and husband Dimitri Petrides were brought in as consultants to advise Germany’s professional body, the PTA. She suggested that the mambo styling of the Cubano would generate greater possibilities for choreography. More people converted.

Vernon Brock, Bobby Medeiros and Sam Sodano took Latin to new heights

Another dichotomy put rumba into a spin in the 1970s when an American contingent including Vernon Brock, Bobby Medeiros and Sam Sodano took Latin to new heights. They brought a rich cultural heritage, fused with authentic Latin styling and a new conveyance of performance into the competitive arena. It generated more hip action and body isolation in the rumba, which the traditional English school initially refused to accept.

Brock, who had a background in musical theatre and was later dubbed the Bob Fosse of the ballroom, often used his choreography to perform to the audience rather than the tight circles preferred by the European couples.

Sam Sodano tells Mayer-Karakis in Ballroom Icons that he was warned by a former World Latin champion: “If you do hip movement in the rumba at Blackpool, they won’t look at you, you’ll be disqualified.”

But by that time Nina Hunt, renowned for training a stable of champions, had started to warm to the new elements. She was reputed to have captured the Americans on 8mm film during the practice session for the 1972 British Open and her pupils were soon emulating the choreography and performance technique.

Brock talks about this in Ballroom Icons: “People asked if we were mad about that, but we thought it was actually quite flattering.” As a consequence, the styles fused and the rumba again underwent a metamorphosis.

Another key milestone on rumba’s journey was Sammy Stopford’s basic rumba at the British Open in 1987. There was a great competitive rivalry between Stopford and Donnie Burns, and Blackpool was often a cause for sensation where those at the top of their game delivered something extraordinary.

Latin had been evolving against a backdrop of cultural and musical influences

The legacy of Saturday Night Fever and the emergence of Michael Jackson still featured heavily in the choreography.

Says Brigitt Mayer-Karakis: “We all did it and looking back some of that choreography now looks slightly comical. What Sammy did bucked the trend. He took to the floor, stood there for what seemed an incredibly long time and then performed a very basic rumba – alemanas, openings out. He just kept it really simple and the crowd went wild.

“Psychologically, that response unsettles your opponents. To have the crowd on your side is a force to be reckoned with.”

Stopford’s partner Barbara McColl remembers the moment: “It wasn’t planned. We’d been working on a very different rumba, which was more passionate, more aggressive, but that year the orchestra had introduced some new pieces including a rumba to Phantom of the Opera.

“Our choreography simply didn’t match the music. We stood there for a moment and then reverted to basics.” The couple’s performance brought the audience to its feet. They won the rumba and were placed second over all. Donnie Burns and Gaynor Fairweather clinched the trophy.

So what of the rumba today? Mayer-Karakis believes contemporary dance and ballet is fusing with Latin and this is particularly prevalent in rumba. “It’s now more about movement than storytelling, stretching and shaping the body while staying true to the nature of the dances,” she says.

A former Latin champion herself, she concludes that rumba was her favourite dance. “For me, rumba was very personal. It’s about expressing your personality. I wasn’t as well equipped as some of my opponents for speed and tricks and the slowness of the rumba gave me the opportunity to project myself as a strong, independent woman.”

©by Alison Gallagher-Hughes