This article first appeared in a series called Perfect 10 in Dance Today (www.dance-today.co.uk)

by Zoë Anderson

The waltz is one of the oldest of ballroom dances. Across its long history, this dance has been both scandalous and sweetly nostalgic, always associated with romance. The obvious characteristics of the modern waltz are its music, in ¾ time, and its flowing, graceful turns.

The waltz was always a turning dance: the word means to turn or to roll. The first recorded use of “waltz” as a dance term appears in 1748, in a ban on the Ländler, an Austro-German folk dance. Another ban, from 1760, refers to “German waltzing dances”, covering a range of turning steps.

Why were they banned? Turning dances were couple dances, with the beginnings of ballroom hold. Pairs of dancers faced and held each other, hanging on close to keep their balance as they swung through the fast turns. This was an unusual level of physical intimacy, at a time when most dances were performed side by side. The waltz was shocking – and remained so, with generations of moral panic to come.

In 1771, the German novelist Sophie von La Roche made one of her characters exclaim over the dance, now being performed by aristocrats:

“He put his arm around her, pressed her to his breast, cavorted with her in the shameless, indecent whirling-dance of the Germans and engaged in a familiarity that broke all the bounds of good breeding”.

The turns and the physical closeness made the waltz a giddily exciting dance to perform. In 1774, Goethe suggested its intoxicating effects in his hugely popular novel The Sorrows of Young Werther. When the sensitive hero dances with his beloved Lotte, “I felt myself more than mortal, holding this loveliest of creatures in my arms, flying with her as rapidly as the wind… I vowed at that moment, that a maiden whom I loved, or for whom I felt the slightest attachment, never, never should waltz with anyone else but with me, if I went to perdition for it!”

In 1774, the waltz was still new: Werther notes that many couples weren’t sure how to dance it. By 1802, it had spread from Germany and Austria to Paris, where an anonymous British pamphleteer caught sight of it.

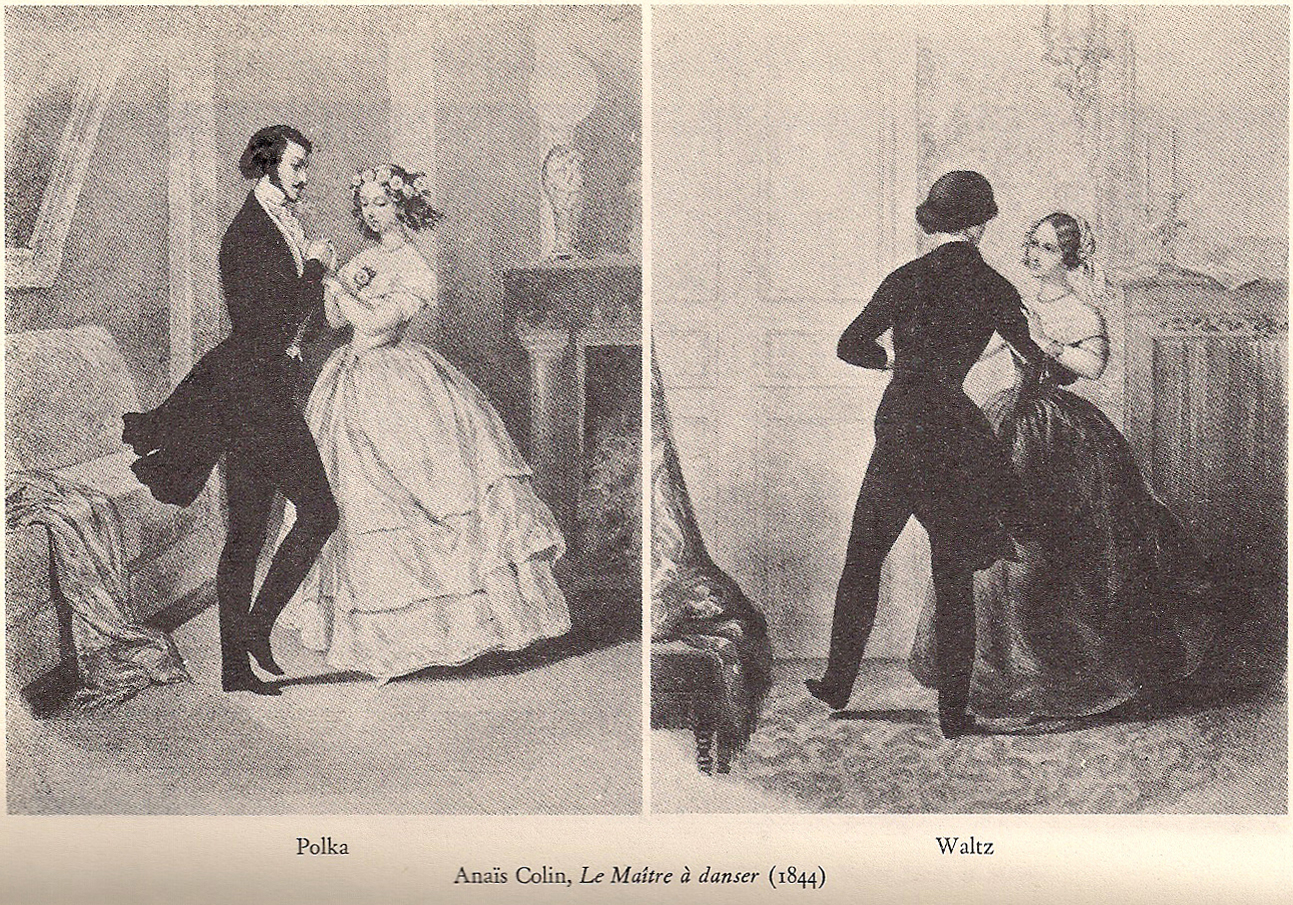

“The dance was of so curious a nature that I must describe it… they keep turning each other round and round, till they have completed the circle of the whole platform, in the manner of the sketch here presented.”

As the sketch shows, the partnering hold of the modern waltz had yet to develop. Dancers faced and held each other in a variety of grips and poses, recorded in contemporary cartoons as the waltz caught on across Europe.

The dandy Thomas Raikes remembered: “No event ever produced so great a sensation in English society as the introduction of the German waltz in 1813… Old and young returned to school and the mornings, which had been dedicated to lounging in the park, were now absorbed at home in… whirling a chair round the room, to learn the steps and measure of the German waltz… The anti-waltzing party took alarm, cried it down, mothers forbade it, and every ball-room became a scene of feud and contention…”

Mothers were not the only protesters. The poet Lord Byron, himself notoriously “mad, bad and dangerous to know”, was ready to be shocked by the abandon of the dance. The Waltz: An Apostrophic Hymn, which he published anonymously in 1816, has lurid descriptions of the early ballroom hold:

Round all the confines of the yielded waist

The strangest hand may wander undisplaced;

The lady’s in return may grasp as much

As princely paunches offer to her touch…

Say – would you make those beauties quite so cheap?

Hot from the hands promiscuously applied,

Round the slight waist, or down the glowing side,

Where were the rapture then to clasp the form

From this lewd grasp and lawless contact warm?

He “princely paunch” is a jibe at the overweight Prince Regent, who in 1816 included the waltz in a royal ball. This confirmed its acceptance by the British establishment, but The Times was horrified to see this “indecent foreign dance” at court. “National morals depend on national habits: and it is quite sufficient to cast one’s eyes on the voluptuous intertwining of the limbs, and close compressure of the bodies, in their dance, to see that it is indeed far removed from the modest reserve which has hitherto been considered distinctive of English females…

we feel it a duty to warn every parent against exposing his daughter to so fatal a contagion.”

Parents did expose their daughters, though they were careful about it. At Almack’s, London’s most exclusive society club, young ladies could not waltz until they were given permission by one of the club’s aristocratic patronesses. The waltz was to become a standard part of upper-class matchmaking, with parents keeping a sharp eye on who danced with whom. Queen Victoria, the embodiment of respectability, did waltz – but, as one obituarist noted, usually with visiting royals, and with her husband.

There were different styles of waltzing. The Viennese were famously speedy, dancing on the flat foot, gliding and spinning as fast as possible. In France, dancers would waltz on tiptoe. By the mid-century, pictures show dancers in what is recognisable as modern ballroom hold. Leader and follower became firmly defined gender roles.

“It is recommended that the lady, when waltzing, leave herself to the direction of her partner, trusting entirely to him, without in any case seeking to follow her own impulse,” advised Hillgrove’s Ball Room Guide in 1864.

“A lady is reputed so much the better dancer or waltzer as she obeys with confidence and freedom the evolutions directed by the gentleman who conducts her.”

While the waltz dominated Victorian ballrooms, it remained a demanding dance, its whirling steps requiring floor craft and musicality. There was also a real danger of dizziness. In the modern waltz, dancers alternate between “natural” turns (to the right) and “reverse” turns (to the left), with a change step in between. Victorian waltzers tended to spin in one direction, clockwise, as they went around the ballroom.

In Victorian Britain, “reversing” was a controversial issue, partly because the man had to grip his partner tightly to change direction. The move was variously seen as daring, unaristocratic and difficult; it was even forbidden at court balls. Overseas, and further down the Victorian social scale, the technique was happily accepted.

If the British upper classes were reluctant to reverse, they were open to variant steps. The original valse à trois temps faced competition from the modified valse à deux temps. Instead of taking three steps, to match the one-two-three of the music, the dancer would take a long step on the first two beats, then step together on the third. More accomplished à trois temps waltzers looked down on this simpler version; in the US, it was even nicknamed the “Ignoramus” waltz.

Though some moralists still worried about its close contact between dancers, the waltz was now praised for its refinement. In 1884, the etiquette manual Manners and Social Usages called it “the most fashionable, as it will always be the most beautiful, of dances. Some of the critics of all countries have said that only Germans, Russians and Americans can dance it. The Germans dance it very quickly, with a great deal of motion, but render it elegant by slacking the pace every now and then. The Russians waltz so quietly, on the contrary, that they can go round the room holding a brimming glass of champagne without spilling a drop.”

At the start of the 20th century, the waltz was overshadowed by new American rhythms.

Even when music was in time, dancers didn’t stick to traditional waltz steps. The Boston, danced to waltz music, had a smooth walking motion, rather than the rotating steps of the Victorian waltz. During World War I, the “Hesitation” waltz became popular, adding a syncopated pause.

The Dancing Times suggested that the waltz had been neglected because it was difficult. During the war, “young men, few of whom had had dancing lessons, found the foxtrot so much easier to pick up in the short space of their 14 days’ leave… For some time after the Armistice the majority of dancers used foxtrot steps whenever a valse was played”.

In peacetime, with a dance boom, the waltz enjoyed a revival, pushed by British publications. In 1921, the Dancing Times called a conference of dance teachers; one of the issues discussed was the decline of the waltz, and the lack of a standard technique. The conference helped to establish the modern standard – sometimes called English – waltz.

In a competition held by the Daily Sketch in 1922, waltz and foxtrot categories were firmly separated. “The good that that competition did cannot be over-estimated,” argued the Dancing Times.

“It formulated the axiom that the valse and the foxtrot should be interpreted by different steps, and the dancing public began to take the valse seriously and to discover how much more enjoyable it could be made if danced properly.”

As the modern waltz was defined and standardised, it could be firmly contrasted with the Viennese waltz. The major difference is speed. The standard waltz is now a slow dance, with 30 bars per minute, where the whirling Viennese has 60.

Whether it flows slowly or quickly, the waltz is now an elegant and romantic dance. In competition, dancers can aim for both the smooth grace admired in the 19th century, and the ardour that Werther felt when he span with Lotte in his arms.

© Zoë Anderson