This article first appeared in a series called Perfect 10 in Dance Today (www.dance-today.co.uk)

By Marianka Swain

“Of all the ballroom styles, this is the one that most requires you to be an actor as well as a dancer,” observes Gary McDonald, executive board member of the World Dance Council. Teacher Harriet Nelson agrees: “Unlike other dances, there isn’t really a ‘paso lite’ – a social version suitable for a crowded floor. You have to commit, wholeheartedly, to its violence and passion, to playing those specific roles and to evoking the most dramatic story in the ballroom world.”

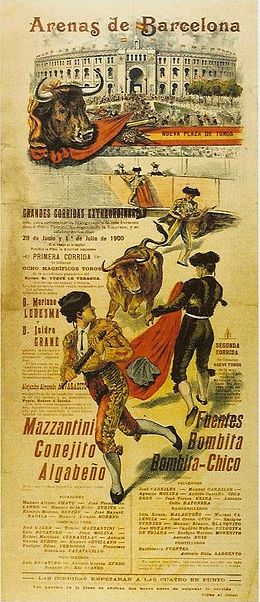

This dramatic content makes the paso doble one of the most well-known of the standard ten dances, as renowned for its association with sunny Spain, the charging bull, the swish of the matador’s cape and blood in the sand as for any dance steps. However, it’s also a dance curiosity, for if you start to examine the figures of this hot-blooded Spanish explosion – coup de pique, sur place, huit – you’ll soon discover that it owes as much to France as Spain in its terminology and origins.

The dance, of course, draws on the tradition of bullfighting, which can be traced back to prehistoric bull worship and sacrifice and to one element of Roman gladiatorial games, before it was adopted as a distinct pastime in Spain and its central and South American colonies, popularised as a sport on foot (as opposed to horseback) by Francisco Romano in the 1720s.

“In the 19th century, corridas became increasingly popular in southern France, and it’s this influx of Spanish culture that inspired the creation of the bullfighting dance,” says Gary. “But the tempo and regular 2/4 beat are most likely drawn from a popular French military march called ‘paso redoble’, or ‘double step’, similar to ‘paso doble’ or ‘two step’.”

“The combination of marching beat and speed – 62 bpm at competition level – make it very different to any of the other Latin styles,” explains Harriet. “Its regularity means every step is distinct, like determined speed walking, as opposed to the jive’s easy swing or the samba’s undulating syncopation. That presents two challenges to the dancer: firstly, to maintain that relentless pace, and secondly, to add shaping, variation and drama to this martial baseline.”

Fortunately, the paso doble has a rich cultural backdrop. Although it was shaped into a ballroom style in France, the dance’s origin lies in the tradition of the torero, or bullfighter, making an extravagant entrance into the ring (known as the paseo), which included rousing music and some dance steps, and in the drama of the passes (or faena) made just before the kill, which, like a Hollywood movie, were emphasised by a stirring soundtrack.

This practice was interpreted by French instructors and dancers at the beginning of the 20th century, taking elements of these traditional torero dances, including flamenco action, and combining them with partner dance interpretations of the drama of the bullring. The name paso doble, or “two step”, refers to the emphasis in the time signature: two emphases per bar, so in 2/4 time signature, the dancers stress “one” and “three”, and in 2/6, they stress “one” and “four”. This fledgling form was popularised in bullfighting pantomimes, common in the 1920s, with the man playing the bold, arrogant torero and the woman the elegant cloth or capa.

However, the paso doble owes its inclusion in the ballroom canon to renowned French dancers, instructors and Latin ISTD founders Pierre Zurcher-Margolle and Doris Lavelle, who made it the toast of Paris in the early 1930s and then took it to the UK as the newest fashion in partner dancing, placing it alongside cha cha cha, rumba and samba in their repertoire.

Paso doble has never been adapted as a social dance, but it survived as a competition style,

“most likely because of its test of partnership, performance, energy and commitment,” believes Harriet. “It requires great strength from both dancers – although it’s often thought of as the man’s dance, the follower takes a dominant role in some of the flamenco figures – but it’s a real balancing act: too much power and passion and you lose control of it; two much attention to detailed lines and shapes and you lose the emotional impact.”

Part of the appeal for dancers is the creative process of shaping the story through this balance of battle and seduction, violence and artistry, brutality and beauty. Unlike most other ballroom styles, the figures have a distinct narrative purpose, informing the audience who or what they’re seeing on the floor: a brave bullfighter, steeped in tradition, a proud, sultry gypsy girl, a billowing cape or a rampaging bull.

Danced correctly, the steps tell the story, such as the appel or foot stamp, which would raise dust in the ring to get the bull’s attention; the chassé cape, in which the man leads his partner from one side of his body to other to mimic the bullfighter’s caping motion; and the coup de pique, which evokes the stabbing motion of the bullfighter.

Dancing the paso doble, however, is not just stamping, cape waving and stabbing, notes Harriet – “that’s a common misconception! The body positions and lines are very specific. The leader represents the bullfighter, who manipulates his body to attack the bull while minimising counter-attack by twisting out of range and presenting a smaller target, and the capework, both with an actual cape and with the follower acting as the cape, draws on folk tradition, so it’s a proud art form.

“Also, as the paso developed, dancers added more Spanish courtship elements, with the woman taking on the role of señorita in addition to cape and bull, so in certain figures, it’s a dance of flirtation with the same rules for specific flamenco movements as you have for Cuban motion or samba bounce.”

The narrative shaping and flamenco feeling is crystal clear in the most popular paso doble music, Pascual Marquina Narro’s rousing “España Cañí”, composed in 1925, which has notable highlights. “It’s the perfect music for this dance,” says Harriet. “It commands attention, it requires a polished, detailed routine with extravagant climaxes for the highlights and it challenges the dancers to match the martial beat, stirring passion and dramatic heights; anything less will fall flat. Like the bullring, paso doble is not for the fainthearted.”

©Marianka Swain