A Conversation with Eduard Strauss (2025) at the House of Strauss

In 2025, Vienna celebrates 200 years of the Strauss dynasty ~ a milestone that highlights how profoundly this family has shaped the city’s musical and cultural identity. In this anniversary year, Bibi Jung offers a remarkable and sensitive conversation with Eduard Strauss that goes far beyond a historical interview. With great attentiveness and personal depth, she opens a window into the human, social, and emotional forces behind the legendary music. This dialogue allows us to experience Strauss not only as a dynasty of sound, but as a living family story woven into Vienna’s past and present.

Text & Interview: Bibi Jung MA (click here for German version)

Prof. Dr. Eduard Strauss (born 1955, Vienna; studied law and works as a civil judge and president of the senate, currently head of the Vienna Institute for Strauss Research)

Photos: Bibi Jung MA, House of Strauss / Strauss Archive

As the granddaughter of a composer and coming from a family of musicians myself, it was a special pleasure for me to meet Prof. Dr. Eduard Strauss in person for an interview.

Much is known, preserved in museums, and documented, but the time spent with the great-grandson of the Strauss family gave me a particularly intimate and family-inherited insight into the era, the role of women, and the background of composing during that time.

The Strauss dynasty continues to shape Vienna to this day. Yet behind the glitter of waltzes and the shine of operettas lie family conflicts, economic pressures, and strong women working in the background.

In the interview, Eduard Strauss (2025) – Eduard I was his great-grandfather, Johann II his great-granduncle – speaks about courage, history, power, and the business of music.

⸻

The Story Behind the Sound

“I am asked less as a musician today,” says Eduard Strauss, “and more as a historical expert.”

His mission: “You cannot understand the music without the history.”

Compositions are not isolated works of art but reactions to life circumstances – both private and societal.

The era in which the Strauss family lived and worked was one of the most exciting and contradictory periods in Austrian history. It shaped not only society but also the development of popular entertainment music, a field in which the Strauss family achieved global prominence.

The period was characterized by political censorship, which forced people to retreat into domestic life.

Private music evenings and dancing became an outlet – the very embodiment of joy. In exactly this atmosphere, the Strauss dynasty began to elevate Viennese dance music to new heights.

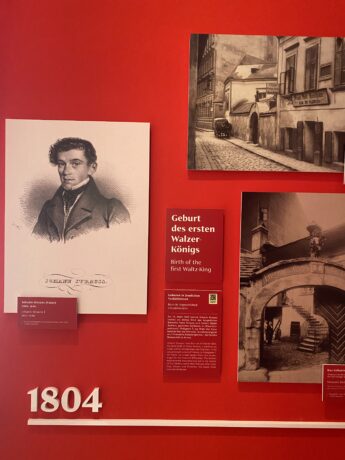

Johann Strauss the Elder placed himself politically on the side of the imperial house and was one of the first to recognize the opportunities that came with it.

He turned dance music into a professional business — complete with orchestra, tours, and music publishing.

⸻

The Mother Anna: Brave, Clever, and Uncompromising

When the father left the family, the mother fought for the survival of the children – with a determination that was extraordinary for women in the Biedermeier era.

A key date was 31 July 1844:

• Johann Strauss the Younger officially registered with the Vienna magistrate his intention to become a musician.

• On the same day, the mother filed for divorce.

“A radical act – filing for divorce in 1844 was courageous and socially dangerous.”

She remained the center of the family – strict, controlling, and economically shrewd.

The Biedermeier era was shaped by domesticity, morality, seclusion, social control, and a rigid role model for women.

“Without a strong woman like Anna Strauss, the Strauss dynasty would not have been possible.

She trained the sons musically, even though Johann the Elder actually forbade it.

She was the key figure who encouraged Johann Strauss the Younger (the later Waltz King) to pursue music.”

Summarizing the women of the Strauss family – including the sisters of Johann, Eduard, and Josef, Anna and Therese:

• Invisible pillars: The sisters ran the household and organized everything in the background.

• No room for emancipation: Musical training or careers were denied to them.

• Dependence: Their livelihood was secured through the will – under strict conditions.

• The mother: One of the very few women of the time who divorced, and she bound the daughters to the musical welfare and business interests of the family, which is why they never married.

⸻

When Brothers Become Rivals

Contrary to the romanticized idea, Johann, Josef, and Eduard Strauss rarely worked together.

Joint works such as the Trifolien-Walzer remain the exception.

“They only came together for business – not out of family harmony.”

The famous Strauss brothers were primarily competitors in the same market.

“The boss was Johann Strauss the Younger, and everyone had to dance to his tune.”

Composing was a task, a business. But how did composing actually work?

“Johann Strauss the Younger probably composed from the violin, some from the piano, and preferably standing at his desk at night! Later he was gifted a harmonium. Its sustained chords motivated him to compose and to write.”

⸻

From Poor District to World Fame – and the Fear of Falling Back

The social ascent of the Strauss family was enormous – but accompanied by constant worry.

“Johann Strauss the Younger had a panic fear of becoming poor again.”

Money, security, and the survival of the family were central driving forces – far more than artistic inspiration.

Although at the peak of his fame he earned 3,000 guilders for the Gartenlaube-Walzer, the fear never left him. That was likely also the reason for the constant composing.

“Music was always work – at home they made music, but not out of family joy. Rehearsing, copying, arranging. Something had to be finished every day.”

The ball season created additional pressure: a short, intense period in which the business had to function.

As Vienna grew into a larger city, the demand for balls, events, artistic evenings, and concerts also increased.

Dance music became an expression of joy in a politically charged time – and it connected all social classes.

⸻

1867 – The Year of the Blue Danube Waltz

The year 1867, the year of the Blue Danube, was shaped by diseases such as cholera, a lost war, and further shaken by an economic crisis.

The Strauss family responded with 25 new compositions.

“They wanted to lift people out of difficult times – with music that gave courage.”

Johann Strauss the Younger composed the Blue Danube Waltz (An der schönen blauen Donau), which became a symbol of joy, lightness, and the hope of a new beginning.

The escape into dance and pleasure was possible for people of all classes; it carried no political meaning and created a sense of community.

The original lyrics of the Blue Danube were a satirical critique of Vienna – far from nostalgic glorification. But people didn’t care; they wanted hope, and the waltz gave them hope for better times.

Music and dance were a social therapy.

When the waltz premiered in 1867, music and dance brought new brilliance to Vienna.

⸻

Marketing Geniuses of the 19th Century

Strauss the Elder and the publisher Haslinger invented something that seems obvious today:

The composer’s portrait on the sheet music.

An early form of branding – and a major success factor with the ladies in the Volksgarten.

⸻

Are There Still Unpublished Scores from the Strauss Era?

“No, the business model was simple: the composer and the publisher signed a contract in which the composer committed to delivering a certain number of waltzes, polkas, or marches per year.

The composer delivered the scores in a clean final copy, a so-called Schönschrift. The publisher paid, and the works belonged to the publisher. From these, variants were then produced – for harp, for two violins, etc. There were no recordings back then; everything had to be protected manually.

Everything was live!”

⸻

The Standing of the Waltz

The waltz was originally a scandalous, far too intimate, fast, wild turning dance, which after the early 19th century became Vienna’s musical trademark.

At the Great Redout of the Congress of Vienna, in the Hofburg ballroom, and later in the Redoutensaal, the waltz was fully established, beloved, and danced by all social classes – from high nobility to the lowest working classes.

“But of course, the high gentlemen also enjoyed going to the washer-women’s balls, especially masked balls – those were wild!”

“Waltz was danced everywhere” – it was the triumph of the people, the ball dance par excellence.

The waltz was (and is) not only artistically and socially fascinating but also extremely beneficial for health.

The turning, swirling, sensual nature of the dance has physical, mental, and emotional effects. People felt that then and feel it today.

Today, the waltz teaches us balance, posture, and trains muscles and the cardiovascular system. But its physical benefits have long been surpassed by the mental and emotional ones – such as concentration, stress relief, and simply joy and sensuality.

“The aristocracy was quite relieved that they no longer had to dance the stiff minuets but could dance the waltz, which offered more opportunities for touch and more sensuality.”

And today the waltz remains revolutionary, enchanting millions with its musical variety, fitness qualities, and liberating joy of life.

⸻

Strauss on Tour – With Dance Instruction!

“But the business trips of Strauss the Elder were special: in addition to the orchestra, there was always a dance teacher present who instructed the audience on how to dance.”

It was live teaching with live music.

⸻

The Emperor Waltz and Its Secrets

“The Emperor Waltz is not only a festive waltz but also full of musical subtleties and hidden secrets that Johann Strauss the Younger deliberately included.”

Some famous works contain concealed musical messages.

“In the coda of the Emperor Waltz you can find the imperial anthem – but only audible if you reverse the horn part to clearly hear the melody. Two versions were composed: a concert version and a dance version.”

For musicians, this is a particularly special experience; in the dance version this passage is omitted – it would simply not be danceable.

Johann Strauss the Younger masterfully connected composition, danceability, and political messaging.

⸻

What About the Waltz’s 3/4 Time? How Did Strauss Arrive at It?

“The 3/4 time of the waltz comes from the Ländler and was perfected for Vienna’s urban dance culture by the Strauss family and other composers. It was no longer just hopping – the goal was turning.”

It is the 3/4 rhythm that makes the rotation, floating, and sweeping quality of the waltz possible.

⸻

Finally, the Question: Was Strauss Primarily Interested in Musical Composition or in Dance Music?

Eduard Strauss smiles.

“Always dance. Strauss was a dance musician – from the first to the last note.”

Concert versions came later. The origin always lay on the dance floor.

⸻

Thank you for a lovely personal conversation and for your time!