By Nicola Rayner

This article first appeared in a series called Perfect 10 in Dance Today (www.dance-today.co.uk)

In the ballroom, the tango is unmistakable. Even its name – the hardness of the consonants – suggests a dance with attitude: one very different from the four other standard ballroom dances. It is easy to tell when a couple is dancing the tango: it is the ballroom dance in which they do not smile. As Kapka Kassabova writes in Twelve Minutes of Love:

Couple dancing is joyful, relaxed, extroverted, uncomplicated and upbeat. Moving to it makes you laugh and forget your troubles… Not so with the tango. The tango is all about your troubles.”

There are other clues too, of course: “There is no rise and fall,” says Kele Baker, who teaches International, American and Argentine tango, and choreographs the Argentine tango routines for “Strictly Come Dancing”. “In the swing dances you have rise and fall; in quickstep, foxtrot, waltz and Viennese waltz there is an up-and-down texture to the dances, but none of the tango dances have any rise and fall.”

There are other key differences: in the ballroom tango, the hold is more compact, knees are flexed. “There’s a martial quality to it,” says Kele. “There’s almost a competition between the two dancers; there’s an argument going on, and so you look for that strength, that power, that fierceness, which is completely different to, say, a slow waltz, where you want elegance, softness, roundness, romance – no one’s fighting with each other.”

The martial quality can be found in the music. Says Kele: “Traditionally, tango music has a strong one-two, one-two beat – a bit like marching: oom-pah, oom-pah – with the strong beat being the first beat… That’s the core that runs through it. Some music is written in 2/4 timing and some music is written in 4/4 timing.”

Interestingly “La Cumparista”, the most famous of tango tunes, was written as a march, by a bunch of Uruguayan students. Kassabova tells the story: “A little march-like tune started up on the students’ tamboriles or drums. It stuck. Pam-pam-pam-pam, tarararara, tam-pam-pam-pam.” (Kassabova’s brilliant phrasing immediately calls the tune to mind.) Soon after, in 1917, “La Cumparista” was picked up by the famous orchestra of Roberto Firpo and the rest, as they say, is history.

Today there are many branches of tango

– though perhaps the two best known to British, “Strictly”-watching audiences are the ballroom (or International) tango and the Argentine version – however, the roots of the dance were planted in the Rio de la Plata. It was danced, as Victor Silvester puts it, “among the lower classes in the neighbourhood of Buenos Aires… For many years it was never danced by anybody in Buenos Aires who had his or her good name at heart.”

“It all started with the bandoneón,” says Kele, “which is the instrument, a type of accordion, that was invented in Germany to be used in churches where they couldn’t afford an organ. That migrated with Europeans to Argentina in the late 19th century, where it mixed with tribal music, Caribbean and African music.”

The tango was born in a time of massive change in Argentina. In 1869, Buenos Aires had a population of 180,000, by 1914, its population was 1.5 million. “It was an absolutely flourishing city with lots of money,” explains Theresa Buckland, author of Society Dancing: Fashionable Bodies in England, 1870–1920.

In Social Dance: A Short History Arthur Franks, then editor of Ballroom Dancing Times, points out the African influences in the tango, introduced by slaves who “transplanted it in the River Plate area where it became known as the candombe… There it was quickly adulterated by the movements of other dances, some of them European in origin, but gradually developed a rhythm and style of its own, in which form it became known as the Argentine tango.”

Kassabova is also drawn to this explanation: “Guess what the drums were called in colonial times? Tangó… from the Bantu African word for drum, tambor… The sensual dancing to the beat of tambores started solo, grew into trance-like states, and sometimes ended up in couples or groups.”

However, Theresa warns against simplicity. “There were an awful lot of Italian and Spanish émigrés who went to work in Buenos Aires at the end of the 19th century, so you’ve got a lot of European ways of moving there as well.”

Indeed, the tango’s angst is thought to echo the emotions of the immigrants, mostly young, male, single, who first danced its steps at the turn of the century in bars, gambling houses and brothels.

So how did the tango go from brothels to the ballroom?

Arthur Franks answers that question rather marvellously: “At first a dance of the riff-raff, it was not long before it was tamed sufficiently to gain wider approval.”

During the early years of the 20th century, the tango was danced among Argentinian émigrés in Paris, and spotted by Camille De Rhynal, “who was very important,” says Theresa, of the highly influential dancer, teacher, choreographer and competition organiser.

In 1907, De Rhynal proposed to theatre manager George Edwardes that the tango should be introduced on to the London stage. The story goes that Edwardes sent for Gabrielle Ray, a famous musical comedy singer and dancer, and that, with her assistance, De Rhynal gave the impresario an idea of the dance. However, the reaction was, as Kele laughingly puts it: “Ooh, lovely dance – couldn’t possibly do that.” London was not ready for the close embrace and sinuous allure of the tango in 1907.

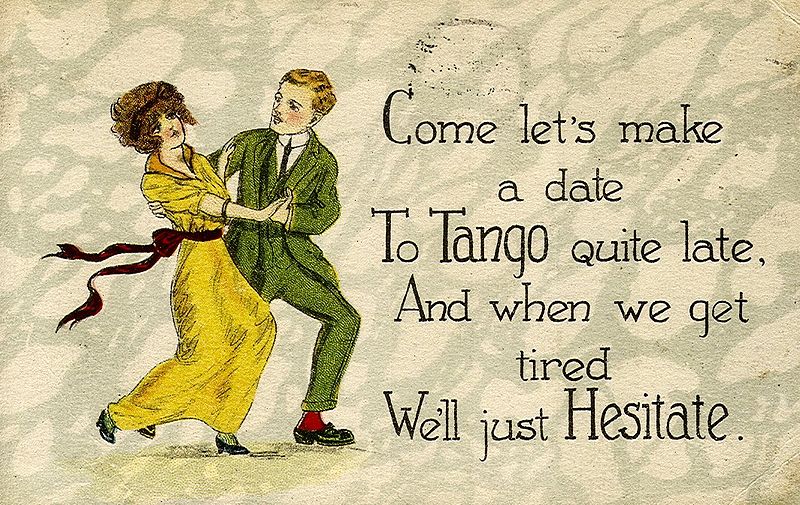

“At that time the dominant dance form was the waltz,” says Theresa, “and with the waltz there’s a sense of romance, but with the tango there’s more a sense of danger and eroticism. The audiences in the West End were quite prudish really – the fashionable ones, at any rate, the middle classes – then there was an outcry when it finally arrived in the UK in the season of 1912–1913.”

In the intervening years, the tango had been tamed by De Rhynal, along with other enthusiasts. “He worked on it down in Nice, because that’s where the aristocrats were, who always in their leisure time wanted something new,” says Theresa. “Celebrities and people of money would go there for their southern Riviera winter and Camille De Rhynal was trying to refine it for the fashionable ballroom.”

The new dance was helped along by dedicated competitions, with one held on the Riviera during the autumn of that very year. The tango returned to Paris. “Embraced by Parisian high society and performed by music-hall stars Mistinguett and Max Dearly,” Theresa Buckland writes, “the tango, now performed to a more romantic habanera rhythm, became the next dance craze to sweep across Europe and North America.”

British dance teacher Belle Harding learned the dance in 1911 at De Rhynal’s Parisian studio and she brought home what she had learned, while interest peaked as holidaymakers returned in the autumn of 1912 from the French Riviera.

The tango had offically arrived and this time London was ready.

“The tango has come at last,” cries a contemporaneous issue of the Dancing Times, whose pages in the years of 1912 and 1913 (the latter was dubbed “the year of the tango”) are filled with tango-mania – advertisements for teachers, dates for upcoming tango teas, the latest on tango music and dresses. There was even a colour. Seriously. “Yes,” Theresa smiles. “It was a particularly bright colour orange – as you know from ‘You’ve been tangoed,’ but then the same thing happened with the polka and polka dots – when there are these crazes there’s a commercial opening.”

However, the tango’s arrival was not without controversy. Theresa says: “The whole business of putting popular social dances on stage is that you have to dress them up a bit – it’s the same as hip hop now, really – and also you need to change them, so that they are visible and attractive in a proscenium arch setting as well.

“So George Grossmith, who was one of the people who popularised it in the theatre, in The Sunshine Girl with Phyllis Dare, learned the dance socially and then it got changed when it went on stage. One of the big complaints was that a lot of people would go to the theatre and think, ‘That’s what I should be dancing,’ and, of course, they were two different things.”

Another problem was the irregularity in the dance. Sometimes the figures were called by their Spanish names, sometimes by their French, and there were countless figures and steps – with a new one for each day of the year, as one journalist at the time put it.

“One of the complaints was that no dancers could necessarily dance together because they’d gone to different teachers and learned different variations,” says Theresa, “which tended to contribute to people going to dances with the same partner, which had not been the case in the Victorian period.”

Dancing Times, with PJS Richardson at its helm, was on hand with advice: “Once the time is mastered, the ‘corte’ or characteristic tango figure will soon be understood. As soon as you can do the ‘corte’, half the battle is won…” (Interestingly, the tango was once indeed known as the baile con corte – the dance with a stop.)

The same passage goes on to outline El Paseo and La Marcha (the slow and the quick walks, still recognisable today); La Media Luna; El Ocho; El Tijeras (the Scissors), and La Rueda (the Wheel) advising: “Smoothness is essential. Avoid all resemblance to the one-step or rag-time.”

The mention of one-step and rag-time hint at what was to come:

With the foxtrot on its way, the tango craze began to wane.

By the summer of 1914, it had lost sufficient power to shock to be danced before Queen Mary, by Maurice and Florence Walton, at her special request.

“It was starting to go on its way out anyway,” says Theresa. “The foxtrot came in, but unfortunately so did World War I. Tango did require that you go for lessons and in war that’s not possible.”

After the war, there was no resurgence of the uproar that had greeted the dance in 1913 when crowded “tango teas” were held in every hotel. “The tango,” writes Victor Silvester rather glumly, “had ceased to be spectacular.” However, all was not lost, he continues: “A year or two after the Armistice, when restrictions on dancing were at last removed in Paris, English dancers were surprised to hear that the tango was once again the most popular dance there. It was a chastened version, however.”

This chastened version drifted over the Channel and sufficient interest was taken for the Dancing Times (described by Silvester as “a staunch supporter of it ever since 1912”) to organise in May 1922 the first of its very successful tango balls, which was attended by nearly 300. The headlining attraction of this ball was the demonstration of the tango by Marjorie Moss and Georges Fontana and the competition they judged.

There followed in October 1922 the Informal Conference, called by the Dancing Times, to discuss the tango. Speakers of note included Camille De Rhynal, Monsieur Pierre, Carlos Cruz and Georges Fontana. “The results of this conference were far-reaching,” writes Silvester. “It was agreed that care should be taken to use only the modern tunes, and that the best tempo was about 30 bars per minute… From this moment, the tango may be said to have been stablilized in this country.”

There was further codification to come with the formation of the highly influential Ballroom Branch of the Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing in 1924, and the series of conferences, called by the Dancing Times, in the 1920s, which have been mentioned earlier in this series.

The following decade saw further stylistic developments. Kele says: “My understanding is that in the 1930s, predominantly in Germany, they adapted the dance and the music. They had big bands – 30- and 40-piece orchestras – and they’re the ones who developed the more martial sound and the dance style that we now know as ballroom tango.”

PJS Richardson in A History of English Ballroom Dancing confirms this, though he sounds unenthused by it, writing: “As originally introduced by Argentines [in] about 1933, this crisp and snappy movement was not unattractive but it was then confined to the legs and feet – the body still preserving its smooth carriage. In Germany this style became very popular and was soon exaggerated and in its exaggerated form crept into England. Mr Camp, an amateur, was one of the first to exploit it.

“Undoubtedly, too, the very theatrical steps of the stage paso doble, in which the movements of a bullfighter are suggested, had a very big effect on the tango. Competitors found that these exaggerated movements, particularly a sudden turn of head when changing direction, earned the plaudits of the spectators if not the marks of the judges.”

Evidently, though, the head snap stuck, but how has the tango developed from the 1930s? Lyndon Wainwright, who danced the tango in competitions and demonstrations in the 1940s and 1950s, observes: “Over the last 70 years tango has changed from a compact dance both in terms of the hold and movements employed…

“The dance now seen on ‘Strictly’ has become more acrobatic, the hold is big and wide, with the lady holding her head much further away from her partner, while the movements are more sweeping, covering a lot more ground. Of course, the traditional Argentine tango has not changed much and has more affinity with the historical form.”

Kele recalls her own tango epiphany in New York, when she was coached by one of the top professionals at the time, Kenny Welsh: “He led me in the ballroom tango figure called the link, one of the most common iconic figures: turn the partner, promenade and a really strong head snap. It should be quite a “crash bang”. He led me “CRASH BANG” and it felt as if my head was not attached; I thought it was going to fly off my body. It was so powerful because his dancing was so powerful. My eyes rolled up and I had a euphoric ‘Wow, that’s what tango can be like: I love this dance.’”

©by Nicola Rayner

My Father Lucien Achille Petrocchi was given licence No 302 by Camille De Rhynal on the 1st November 1935 and won the Tango Competition held at the Hotel Rhual in Nice between the 9-16 February 1936. I have his and his partners photo with their trophies. Do you have any details of this competition?