By Armin Kappacher

Introduction

Quality of movement” is a term which is frequently referred to in teaching, evaluating and judging dancers. Though when looking for a clear definition of this term, things become challenging. And very often one finds opinions filling in for the lack of facts.

It is interesting that in scientific explorations, facts and data are much preferred over “opinion”.

Fortunately though there are several related and complimentary disciplines/areas of exploration to our “Competitive Ballroom Dancing” which provide helpful additional as well as supplemental knowledge to our field.

Such a field is the world of “Somatic Disciplines“, with many different sub groups, such as “Alexander Technique”, “Feldenkrais Technique”, “Rolfing” or “Structural Integration”, “Hubert Godard’s Tonic Function Theory”, “Continuum Movement”, “Body-Mind Centering”, “Craniosacral Biodynamics” and many more.

And there are other extremely helpful and interesting theories or “thinking models” with their origin partially in dance and partially in movement therapy, such as “Ideokinesis” (a term originally created by Lulu Sweigard who researched and developed the ideas of Mable E. Todd), and Skinner Releasing Technique .

The following article provides a good theoretical background on what the challenges are in evaluating and “seeing” movement patterns:

Seeing the Ground of a Movement: Tonic Function and the Fencing Bear

Kevin Frank – May 15, 2003

This article introduces the idea that movement has two parts—a figure and a ground. Figure means in this case the literal action expressed in terms of shape or biomechanics. Ground means the background of the movement that occurs in the tonic system of the mover. In addition, the topic of seeing is considered—seeing meaning here the process of seeing the background to a person’s movement. These ideas are illustrated by a very old story about an unusual bear.

To begin thinking about the “ground” of a movement, consider the observation that we move before we move. The body prepares to do a movement by orienting itself. For example, when I take a breath, before I breathe my back muscles anticipate the pull down of the diaphragm and, if they didn’t, my diaphragm would create some forward collapse of my structure.

As another example, before I raise my arm, my calf muscles prepare by anticipating the change in loading. In both of these cases the body stabilizes itself appropriately to not fall over.

An example of counterproductive pre-movement would be someone tightening his belly to stand up from a chair. In this case, stabilization is making it harder for the person to stand up.

In the first brief moments in which a movement is conceived and prepared for, the essential story of a movement can be predicted. The quality of movement—the flow, the economy, the effectiveness—is determined by how someone consciously or unconsciously sets the tone in the tonic system of his/her body. Thus, to change structure, to change a person’s postural habits and coordination, we need to be able to see and help change the pre-movement embedded in each of that person’s actions.

In the first brief moments in which a movement is conceived and prepared for, the essential story of a movement can be predicted. The quality of movement—the flow, the economy, the effectiveness—is determined by how someone consciously or unconsciously sets the tone in the tonic system of his/her body.

To see another’s pre-movement, it appears we can best do so in a state of resonant empathic observation. We must know these places of preparation in our own body, in order to see it in someone else’s. This point is relevant to any inquiry into how one might teach a bodywork practitioner to see. Teaching seeing means teaching him/her to sense his/her own pre-movement, and to find the perception necessary to change it.

By learning to work with our pre-movement we gain access to the gravity response system that governs our quality of movement.

By learning to work with our pre-movement we gain access to the gravity response system that governs our quality of movement.

Movement that begins with appropriate pre-movement means movement that starts with dynamic orientation to ground and to space. This is the perceptual state in which observation of movement is primarily sensing the ground of a movement, rather its shape. Taking this point a little further, we might consider that part of the body practitioner’s education is relearning the capacity to perceive the ground of his/her own and another’s movement.

Thus, here is a purportedly true story about a Russian nobleman, and a bear that has been taught fencing (swordsmanship). The story introduces the reader to gravity response as the largely unconscious ground that precedes and determines the shape and story of our movements.

From Kleist, About Marionnettes

“I broke my journey into Russia with a visit to the estates of von G., a Livonian nobleman, whose two sons at that time were enthusiastic swordsmen- particularly the elder who had just returned from the university convinced he was an adept.

One morning, as I happened to be in his room, he offered me a foil. We fenced, but it fell out that I was the more experienced, and his passion too bewildered him, so that almost every thrust of mine struck home, until at length his foil flew into a corner.

Half jokingly, half in earnest, as he stooped for his weapon, he told me he had met his match, but then again everything in this world must, and that he should

now have the pleasure of leading me to mine. Both brothers began to laugh and shout “Away with him! Away with him! To the woodshed with him!”

Then they took me by the hands and led me to a bear which their father, old von G., had raised in his yard.

“At my astonished approach the bear was standing on his hind legs, slouched against the stake to which he was chained, his right paw was raised ready to deal a blow; he looked me straight in the eye: this was his way of standing on guard. I thought I must be dreaming, confronted by such an adversary; but no, old von G. suddenly cried “Engage!

Engage! See if you can touch him a single time!”

I made a lunge–once I was somewhat recovered from my astonishment. The bear parried my thrust with the most off-hand riposte. I tried to throw him off with feints: the bear refused to budge. I lunged again with the adroitness of the moment: a merely human breast could not have withstood my steel. With one paw, the bear parried my thrust. Now I was in almost the same position in which young von G. had been.

The bear’s gravity contributed to my loss of composure, as alternating thrusts and feints I began to run with sweat. And all in vain! It wasn’t simply that this bear was the equal of any swordsman in the world at parrying thrusts, but that my feints, and in this no swordsman in the world approached him–provoked no reaction at all; staring straight into my eyes, he seemed to read my very thoughts; he just stood there, that paw at the ready, and whenever my lunges were not in earnest, he refused to budge.”

Why isn’t the bear fooled? If we separate the figure and ground of a movement, we could say that the bear is reading the ground of his opponent; the ground is the state of the tonic system, the management of the center of gravity. When the swordsman is not completely committed to his gesture, as in a feint, he holds back a part of his weight, very subtly, but perceptibly. Before any intentional action occurs, there is a pre-movement.

Another term for pre-movement is anticipatory postural activity (a.p.a), a regulation of the postural system to prepare and adjust for changes in the center of gravity. The a.p.a., an involuntary and unconscious adjustment, precedes voluntary, intentional actions — it is the ground of the gesture. This is why a given gesture can never be given a consistent particular meaning. The meaning of a gesture depends on the tonic activity underlying it. As babies, we are like the bear: we read the state of our parent’s tonic system; and that is how we learn to hold ourselves, in imitation or response to the tonic system to which we are in relation.

Another term for pre-movement is anticipatory postural activity (a.p.a), a regulation of the postural system to prepare and adjust for changes in the center of gravity. The a.p.a., an involuntary and unconscious adjustment, precedes voluntary, intentional actions — it is the ground of the gesture.

Hubert Godard has organized observations concerning the functioning of the tonic system into a theory that he has termed Tonic Function.

In the above story, Kleist’s character states “Affectation appears, as you know, when the soul, vis motrix, inhabits any other point than the center of gravity” In other words, our body language gives us away if we are pretending. Here, body language is defined more specifically as the a.p.a. (the anticipatory postural activity) of the movement.

Learning to see a.p.a is a central skill for a movement therapist, and is useful to many other fields of human endeavor as well. Dr. Rolf, the founder of Rolfing Structural Integration, called this “seeing.” Another important skill is the capacity to infer the perceptual field of the client — to begin to sense the perceptual habits of a client. For, it is only by evoking changes in perception that the a.p.a. will change.

By contrast, teaching movement in terms of voluntary postural adaptations, such as effortful standing-up-straight, interfere with tonic function.

Just like Dr. Rolf, we all may sometimes succumb to this unfortunate strategy.

The fencing bear reminds us that the capacity to see the movement behind a gesture is not a human-invented skill, but rather a part of how all mammals perceive. Our human preoccupations seem to dictate that we must start by noticing our own tonic function in order to perceive it in another.

[…] the capacity to see the movement behind a gesture is not a human-invented skill, but rather a part of how all mammals perceive. Our human preoccupations seem to dictate that we must start by noticing our own tonic function in order to perceive it in another.Source

References:

Kleist, H. About Marionettes. Translated by Michael Lebeck. Mindelheim: Three Kings Press, 1970.

With the importance of having felt and experienced alignment and movement patterns before one is able to see or correct them in another person in mind, the following is an array of visualization exercises based on Eric Franklin’s “Dynamic Alignment Through Imagery”.

Pelvis, Sacrum & Hip Joint

Pelvic arches

- Trace with your fingers the bony structures and compare with the image. Become familiar with the names of different structures.

- Tie a theraband tightly around the pelvis at the greater trochanter height to experience the support effect of the arches. Stand/ walk

- Lying on floor, feel the sacrum drop on the floor, visualize tailbone moving down

- Standing, visualize sacrum like a wedge dropping through the iliac bones

Pelvic balance

- Visualize a carpenter’s level across the ilia. Cause the bubble to be in the center by playing with leveling iliac bones.

- Visualize a horizontal line across both iliac crests, and another one connecting the hip joints. Now plie, and keep both lines horizontal. Do the same with turns. Expand the lines to a square by connecting them vertically – use this as a “grid” to check alignment – being mindful that the square must not tilt.

- Visualize the heads of both femurs as buoys floating on water, the leg being the anchor line and the feet the anchor. Experience the upward float of the buoys and sense the lightness it creates. In a plie imagine the water descending, yet both buoys continue floating.

- Visualize two spot lights at the hip socket. Direct them horizontally, or imagine them being eyes, looking out on the horizon.

Pelvic energy/power

- Pelvic geyser: Imagine the pelvis to be the source of a powerful geyser. Feel the strong energy potential. Feel the geyser first bubbling, then erupting upward through the body.

- Teeter babe: Imagine your pelvis suspended in a teeter babe, with your legs hanging from it.

Pelvic floor

- Breathing: Notice the four delineations of the pelvic floor (sit bones, pubes and tail bone) move apart on the inhale and closer on the exhale.

- Trampoline: Imagine the pelvic floor being a trampoline on which you are bouncing a ball. Do some jumps with this image in mind.

- Drum: Imagine the pelvic floor to be the surface of a drum. Feel it vibrate and resonate. Experiment with walks, jumps and turns.

- Flying carpet: Imagine the pelvic floor being a flying carpet that lifts and supports the pelvis and frees the legs.

Sit bones/ activating deep pelvic muscles

- Rocking the sit bones: Sitting position, rock forward and backward. Increase the speed faster and faster, then gradually slow down again and only visualize rocking. Feel pelvic muscles “come alive”.

- Planting sticks: Imagine your sit bones as planting sticks, pushing into the earth.

- Release tension: Hold buttocks with both hands and pull them straight up without tilting. Hold for a minute, then slowly let go. Visualize them melting down the back of your legs to your heels.

Hip Joint

- Acetabulum controlls femur: Imagine the hip socket to be like a hand, holding the head of the femur. This hand moves the femur with gentle pushes and tugs to initiate leg movement.

- Femoral head spin: Imagine looking at the femur from the rear. Visualize the motion of the femur head in the socket as the leg elevates or lowers. Simulate the femur movement with your fingers.

- Countering in the socket: Watch the surface of the socket move up as the leg rises, and watch the surface move down as the leg lowers. Simulate the socket movement with your hand “cupped”.

- Combination of the two above exercises. Simulate both joint components with your hands.

Iliopsoas

- Fishing pole: Rest position on floor (knees bent). Imagine the leg to be a fishing pole. The lower leg is the string and the foot is the fish. The handle of the fishing rod is in the hip socket. Pull the fish (foot) out of the water, by initiating the action from the handle. During the motion imagine your back, especially the lumbar area spread on the floor.

- Minor trochanter string: Imagine a string attached to the minor trochanter. Initiate the hip folding by pulling the string toward the head . Drop the back, especially the lumbar area, and the neck to the floor like a soft cloth.

- Femur head sinks into hip sockets: Lying on the floor, visualize the femur heads sinking into the hip sockets. Visualize the femur being a wooden pole (broom stick), and the pelvis made of soft clay. Imagine the broomstick sinking into the clay.

- Hip flexion with lower back release: Aas you flex your hip joint, imagine the muscles of your lower back releasing downward. Imagine them melting.

- Rib pulley: Visualize a string attached to the minor trochanter, and that string loops upward over the lowest rib like a pulley. The muscles of the lower back are the counter weight. As you flex the hip joint the counterweights drop.

- Leg swing: Swing the leg from the psoas back and forth for a while imagining the swinging leg to be an extension of the psoas. Then walk and compare the sides.

- Lengthening psoas: Imagine the weight of the leg pulling the psoas long, feel the poas lengthening like taffy. Practice walking with that image.

- Imagine the psoas attaching to the minor trochanter and all the way up to the occiput (connection point between spine and head). Imagine the legs hanging from the occiput.

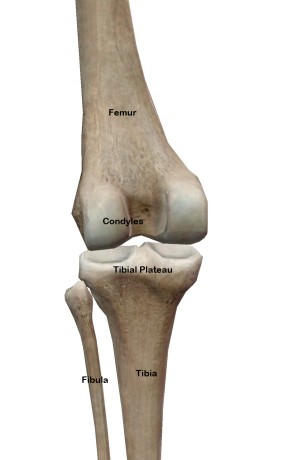

Knee

- Condylar balance: If you sense there is too much weight on the lateral condyles, visualize them as tires being inflated. Inflate the lateral tire until more weight has been shifted to the medial condile. Or the reverse …

- Movement of condyles on tibial plateau: Knee bending makes the condyles move back, knee straightening makes them move forward.

- Movement of the tibia: Visualize the tibia moving backward as you flex the knee, and forward as you extend the knee.

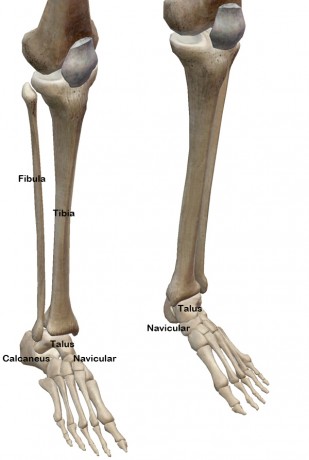

Lower Leg and Ankle

- Ankle tweezers: Hold one foot in a non weight bearing position and visualize the talus suspended from the tibia and fibula like tweezers. Let the foot swing back and forth freely. Imagine the grip of the tweezers loosening more and more to free up more swinging movement.

- Releve: Imagine the tweezers tighten their grip to stabilize the position.

- Hands adjusting talus: Imagine the lower end of the tibia as the palm of a hand the end of the fibula as the fingers. The tibial palm supports the talus and the fibular fingers are in charge of subtle adjustments. Imagine the fingers initiating movement of the foot at the ankle in a variety of directions.

- Relative motion of tibia, fibula, and talus: While performing a plie focus on the changing relationships. As you move down visualize the tibia and fibula moving forward over the top of the talus. Notice that the tibia is mainly responsible to transfer the weight to the talus. Because the fibula travels farther on the outside of the talus, the lower leg turns slightly inward. Or in reverse the talus can be seen as turning outward.

- As you stretch your legs watch the tibia and fibula skim backward over the talus. Because the fibula travels farther on the outside the lower leg rotates slightly outward, and the talus inward.

- Saloon doors: As you point the foot imagine the tibia and fibula as two saloon doors opening in the front, allowing the talus to move forward. As you flex the foot visualize the tibia and fibula as saloon doors opening in the back, allowing the talus to slide backward.

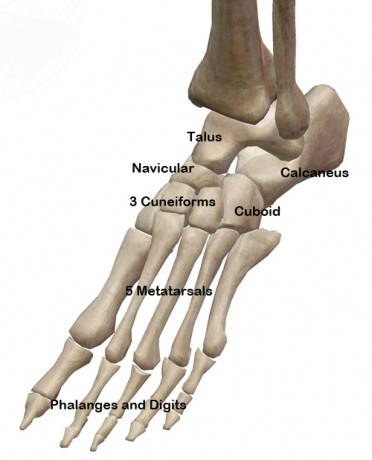

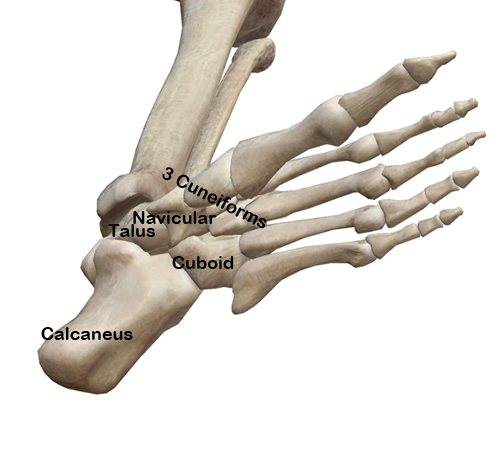

Foot

- Observe somebody else’s foot as they are standing on one foot. Observe the supination and pronation activity.

- Heel pendulum: Focus on the heel making contact with the floor. Visualize the heel being a pendulum swinging from side to side. Gradually decrease the swing until you are exactly on the plum line.

- Imagine waling on uneven ground: Notice how the foot can adjust. Use a small book, or other objects, and walk slowly on/over it, noticing how the foot adjusts.

- Rubber raft: Imagine the foot being an inflatable rubber raft. It can readily adapt to all kinds of waves because it can twist around its longitudinal axis.

- Imagine the talus being the mediator between the tibia, calcaneous, and the navicular. The talus manages all the transitioning forces like a springy rubber ball. To maintain elasticity not any one side of the ball should be subject to constant extreme pressure.

- Foot tripod: Visualize the three main contact points of the foot with the floor (the heel, the distal head of the big toe metatarsal, and the distal head of the fifth toe metatarsal) as a tripod. Distribute weight evenly on these three points. Imagine the points forming a triangle and watch them move further and further apart.

- Foot versus pelvic arches: Focus on the tali of both feet and the sacrum. Visualize these three keystones simultaneously. Visualize how all three keystones are buttressed equally from both sides. Now notice how the pelvic arch lies perpendicular to the long arches of the feet.

- Spreading Metatarsals: Visualize the metatarsals move slightly apart as you put weight on a foot, and notice them moving closer as you lift your foot.

- Toes as feelers: Imagine the toes to be sensitive feelers, testing and exploring the space in front of them.

The “unbendable arm” experiment

These dynamic alignment exercises are constructed in such a way that they help evoke ones sensory awareness of the flow of gravity as well as its opposing force, often called the ground reaction force, through the bone structure. It is the awareness of this bidirectional force which strongly shapes our tonic organization.

These dynamic alignment exercises are constructed in such a way that they help evoke ones sensory awareness of the flow of gravity as well as its opposing force, often called the ground reaction force, through the bone structure. It is the awareness of this bidirectional force which strongly shapes our tonic organization.

This is well illustrated by a modern (and technological) version of a traditional Aikido experiment, known as the “unbendable arm“:

A person is asked to rest their straight arm on somebody else’s shoulder, and first instructed to resist with all their will power as much as possible while somebody pushes down on the straight arm.

Then the experiment is repeated, but the person is now instructed to simply use an image of energy flowing out of the fingers when reaching for the wall, while somebody pushes down on their arm.

Inevitably, by using the image, the person is much stronger and able to keep the arm from bending with ease as opposed to when asked to muster up all of his or her will power to resist.

Electromyography shows that in the instance with “will power”, when the person struggles to keep the elbow joint straight (with no sensation in the hand), he or she is contracting the biceps muscle as well as the triceps. In doing so, the subject is working against him or herself. When the person is asked to use the “image”, the biceps remains free of force, and only the triceps contracts and we can witness the result of an “unbendable” arm.

Clearly the perceptual state influences our motor patterns. The sense of two directions (or in other words, energy passed back and forth along the bone structure as opposed to across the bone structure) allows the antagonists not to get involved, therefore creating a much more energy efficient movement.

There are specific physiological reasons as to why this happens, which are described in

Hubert Godard’s Tonic Function theory (the details of this theory are beyond the scope of this article).

Some conclusions:

What the article about the “Fencing Bear”, the dynamic alignment exercises, and the Aikido “unbendable arm” experiment illustrate in summation, is how the organization and optimization of movement quality, as it is required in high quality dancing, is on one side an extremely complex and involved process. And yet on the other side, quality movement is governed by some clear guiding principals, and we are starting to understand them based on a scientific approach.

Quality movement is governed by some clear guiding principals

The basic ideas of the tonic function theory bring up some perhaps welcome food for thought in our dance world:

Judging

“Seeing” or evaluating human movement hinges on the observer’s internal frame of reference. And this frame of reference has been shaped by which type of movement exploration and education the person has been exposed to. Most dancers have witnessed this first hand, revealed by his or hers changing “tastes” for what they consider good dancing, as they mature in their own movement abilities.

“Seeing” or evaluating human movement hinges on the observer’s internal frame of reference. And this frame of reference has been shaped by which type of movement exploration and education the person has been exposed to. Most dancers have witnessed this first hand, revealed by his or hers changing “tastes” for what they consider good dancing, as they mature in their own movement abilities.

This has far reaching implications on how a person judging a competition will make their decisions, and therefore might be worth considering how judges are selected or certified.

Teaching/Coaching

Purely visual copying of movement patterns is almost impossible, unless the observer intrinsically understands the implications of gravity flow within the bone structure and the brain’s regulation of such forces, mainly (but not only) through sensory awareness. Therefore when teaching and coaching aspiring dancers, a “look at me”, or “visualize a certain movement”, or “change the choreography” type of approach, without reshaping the dancer’s own perception of space, gravity, and emotional stimulus will most likely produce forced and unnatural movement.

And such forced movement will unfortunately be anything but intoxicatingly graceful and utterly grand.

Purely visual copying of movement patterns is almost impossible, unless the observer intrinsically understands the implications of gravity flow within the bone structure and the brain’s regulation of such forces, mainly (but not only) through sensory awareness.

Both, to educate and to evaluate dancers, or for that fact, any high level movement specialist, requires a deep understanding of such principals. A person charged with such tasks must have the skill to “see” accurately.

To see the particular factors which inhibit a person’s movement is not so easy, since it hinges on the observers internal frame of reference which has been established gradually by the persons study and exploration of movement and dance.

Gaining the skill of evoking change in those limiting factors is yet another level of challenge. We may see that someone dances with slight tension in their diaphragm, but what do we do about it? We might see that the dancer’s lumbar lordosis increases when extending the free leg, but how should we intervene? We may witness tension in the shoulder girdle as the dancer uses his or her frame, but how do we help bringing about a release?

Or we may see that the dancer is not within the music, but what advice will bring an attunement between the center’s rate of progression and the rhythmical structure of the music?

These are all really challenging questions, and it becomes apparent, as to why so often opinion is the easy and quick answer to hide behind. In the long term though we only will be able to further develop our field of competitive ballroom dance if we seriously commit to broaden our educational systems. We must devote more resources towards research and development. And we also should be more intent on seeking out collaboration with the many other somatic, movement and artistic disciplines which have made a name for themselves.

Very specific and essential information! Thanks.